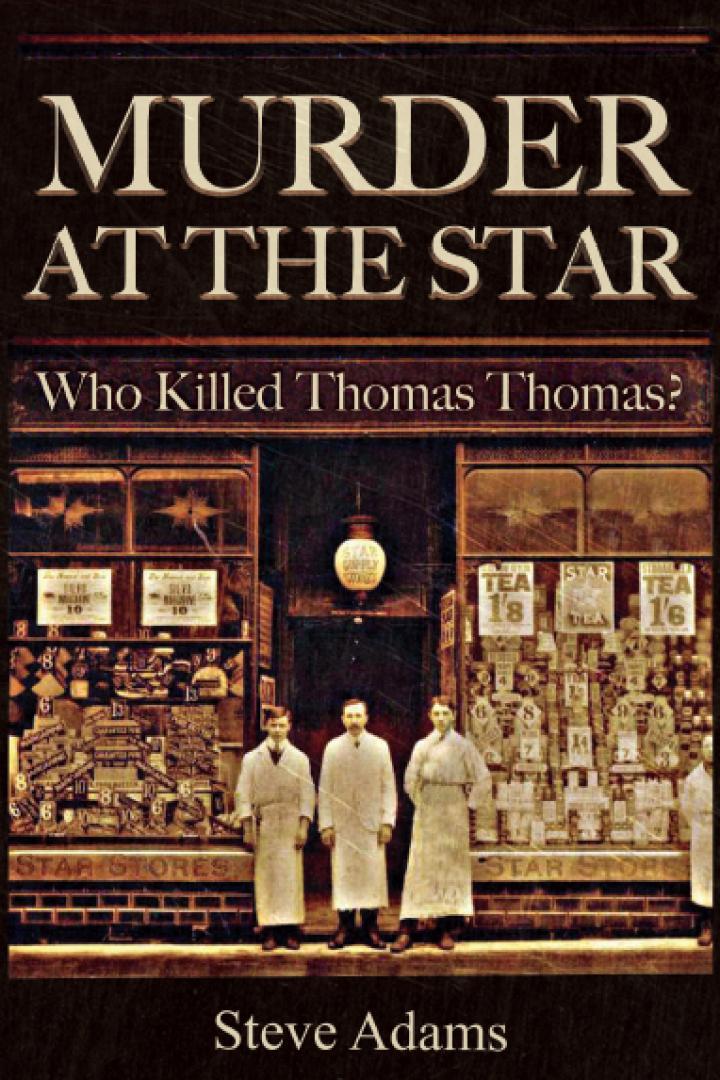

GUARDIAN editor Steve Adams claims he has solved the 94-year-old Star Stores murder. In his new book Murder at the Star, Steve explains the crime and here, he reveals the identity of the killer.

At 10.15pm on Saturday, February 12, 1921, Diana Bowen and her daughters left the fruit shop at Number Three, Commerce Place, in Garnant.

Diana was to be the only adult witness to the murder at the Star.

The Bowens had taken no more than a few steps when they heard a most ungodly noise from inside the Star Supply Stores, the upmarket national chain next door.

“It was an awful screech,” Diana told the Amman Valley Chronicle.

“There was a thud and the sound of running feet.

“I was going to have a look, but after hearing running on the stairs I thought everything was all right.

“I thought the boy in the shop had had his hand in the bacon-slicing machine.”

Shortly after midnight, across the valley at Glanyrafon Villas, Thomas Mountstephens was waiting when Arthur Impey, one of his two lodgers, arrived home from work.

The two men could see the glow through the rear window of the Star where Mountstephens’ second paying guest, shopkeeper Thomas Thomas worked.

Impey suggested that they walk over to ensure all was well.

Mountstephens refused.

An hour later, Impey grew concerned.

Again he urged Mountstephens to accompany him to the Star.

Mountstephens’ second refusal would see him branded a killer for almost 95 years.

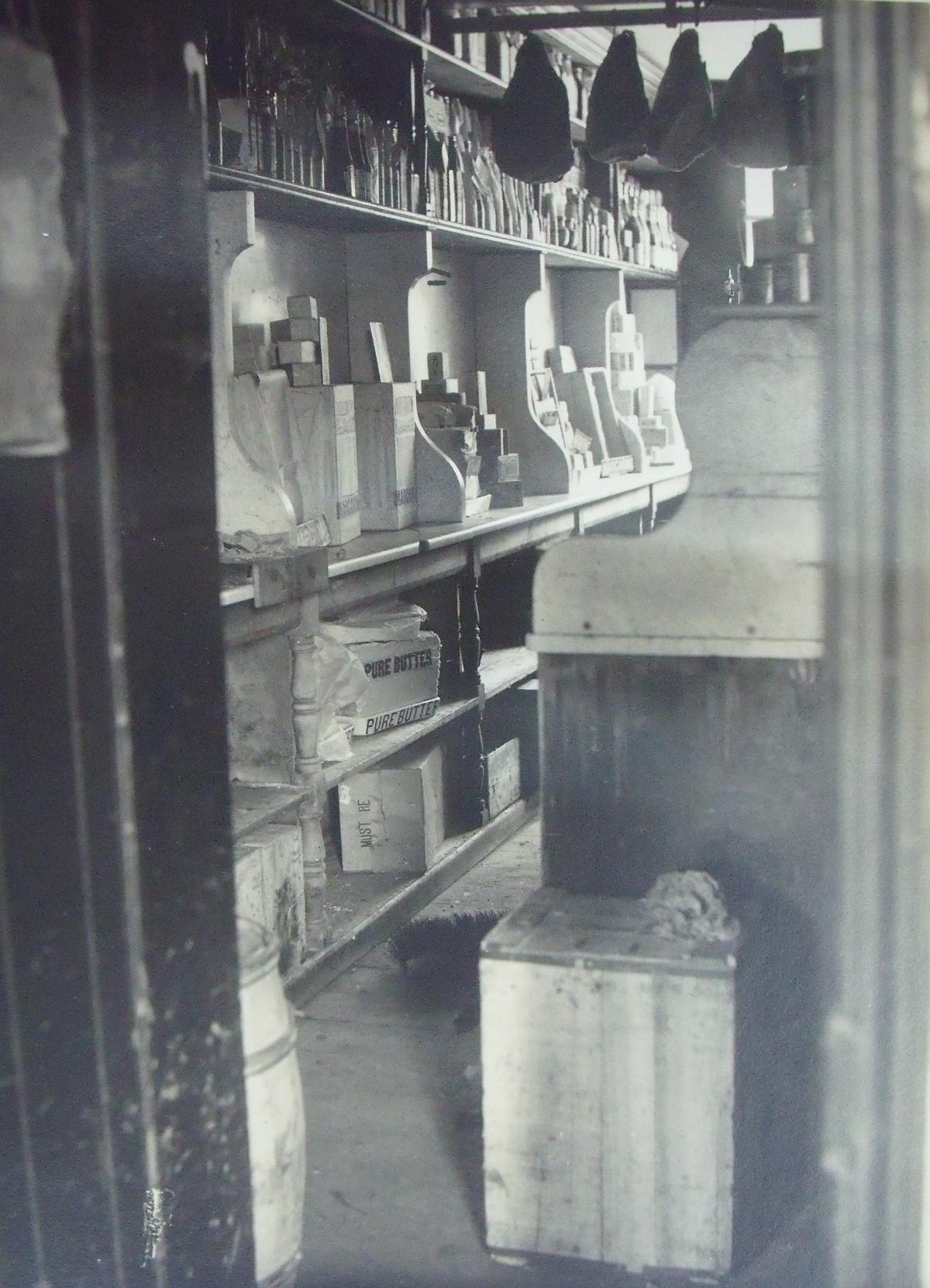

Next morning, Thomas Thomas was discovered murdered behind the counter of the Star.

His throat was slashed and his head battered with such force as to shatter the temporal and parietal bones, and leave 11 separate pieces of bone embedded in his brain. His cheek was also fractured in two places.

His trousers and shirt had been unbuttoned before a knife was plunged into his abdomen and the clothes then refastened.

The shopkeeper’s dentures were on the floor, embedded in a piece of bloodstained cheese.

A broomhead, smeared in blood, was nearby, though there was no sign of the handle. Nor could any knife be found.

The safe was open and £128 and two-and-a-half pence stolen – two days takings for the Star and six months’ wages for a Garnant miner.

A post-mortem, carried out by Dr Evan Jones – the village GP who had studied medicine alongside Arthur Conan Doyle, identified three potentially fatal wounds:

The doctor’s analysis was to prove crucial to the investigation.

The following day, a bloodstained broomhandle and a boning knife were discovered in a nearby stream.

The Metropolitan Police sent one of their most respected men to West Wales

Detective Inspector George Nicholls would one day head the murder squad and be named one of the influential policemen in Britain.

During World War One, Nicholls had been seconded to Special Branch as a spy-catcher. He spoke half a dozen languages and was the man who arrested Charles Wells, the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo.

Nicholls arrived in Garnant on Tuesday, February 15, but the trail was already cold.

The previous day, the woman of Garnant – outraged that the dead man’s blood had been left to cake on the floor of the Star, forced their way into the shop with buckets and mops and scrubbed the premises clean, removing all traces of the culprit and the crime.

Nicholls would spend a month in Garnant, but had little to go on.

There were, he felt, three main suspects: Mountstephens, who had already been convicted in the court of public opinion; Morgan Jeffreys - the landlord of the Star seen at the rear of the building around the time of the murder; and an unemployed miner named Tom Morgan, known to be a liar and a thief.

Nicholls soon eliminated Mountstephens – despite the public feeling against him – and Jeffreys, and turned his attention to Morgan.

Thomas Conway Hewitt Morgan had spent time in a borstal institution as a youth and had been banned from the collieries due to his habit of claiming other men’s work as his own.

There were though two key elements in his favour.

Firstly, he had an alibi.

Most importantly however was the doctor’s assessment that the shopkeeper’s injuries could only have been caused by a right-handed man.

Six months earlier, Morgan had lost the use of his right hand in a bizarre – and unexplained - accident that removed all but his thumb and little finger.

Based on Dr Evan Jones unshakeable assertion, it was physically impossible for Morgan to have committed the crime.

Nicholls remained unconvinced and interviewed Morgan on three separate occasions, but thanks to the Garnant ladies there was nothing to connect him to the murder and no basis to undermine the doctor’s analysis of the injuries.

Had Nicholls been able to cast doubt on the flawed medical evidence he would have been able to prove not only that the murder could have been committed by a left-handed man, but that it must have been.

Rather than clearing him, Tom Morgan would have become one of only ten per cent of the population who could have been the killer – and the only actual suspect capable of the crime.

Then perhaps Nicholls would have questioned why every independent witness named in Morgan’s alibi claimed not have seen him and realised that the one person who corroborated his whereabouts was complicit in a tissue of lies stretching back almost a decade.

Then, and only then, could Nicholls have proved Tom Morgan committed the murder at the Star.

Murder at the Star is published by Seren Books.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here